A Brief History of Houseplants (and Humans)

I’ve always found humans’ continued connection to decorative plants to be endearing and maybe this is just because it’s my job, but it led me to wonder why houseplants have such staying power. Why have humans, for centuries, propagated, collected, cultivated, and cared for house plants at the scale we do?

Early records of houseplants are often traced back to 600BC, the fabled Hanging Gardens of Babylon in present day Iraq. Houseplants denoted class and status for some time in the early days. Those who had the disposable income and time to drape themselves waywardly atop a chaise lounge shaded by a parlor palm, did so. There’s always been a collectors market for rare cultivars, dominated by those with the economic means, but if you thought you were being hustled in 2020 for a $100 cutting of a Pink Princess Philodendron, imagine shelling out $16,000 for a single specimen of an orchid in 1890 (yes, that actually happened.)

Like many bourgeoisie commodities though, people developed submarkets and workarounds for steep prices– native plant material was foraged and grown by middle and working class people– making houseplants more widespread and accessible.

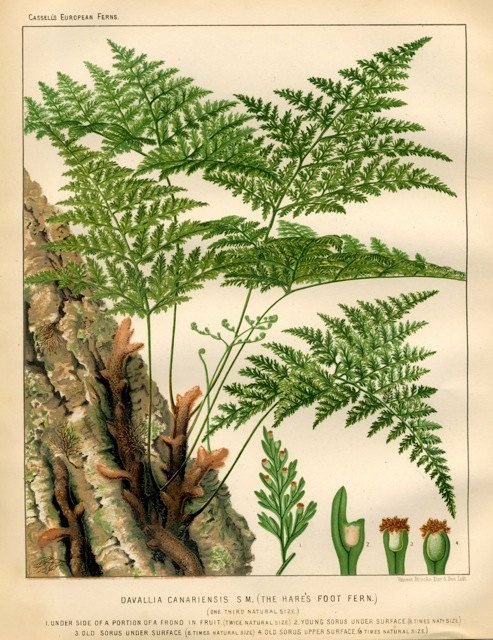

In the Victorian era, Ferns were ravenously popular amongst the aristocracy and working class alike thanks to a fad known as Pteridomania or “fern madness” (an arguably sexist term, only deemed ‘mania' once women got involved, but that’s besides the point.) The accidental advent of the Wardian case– a proto terrarium– launched fern hunting into orbit in Europe and North America. Not only did the glass biomes serve as marvelous environments for ferns, orchids, and other plants to germinate indoors, they revolutionized plant transportation, allowing less hardy plants to survive the journey across oceans at never before seen survival rates. From this, tropical and subtropical plants began making their way around the world and became less expensive.

Wardian cases and the ability to bring plants into homes served as a sort of escapism from 19th century industrialization in Europe and North America. As the cities became more urban and air polluted by factory booms, people sought a means to feel close to nature again. Sound familiar?

Transformative human development has always seemingly coincided with houseplant booms. In 1940’s America, more women began to enter the workforce while men were overseas fighting in World War II.

Along with a zeal for impending economic freedom, they brought small flowing and trailing plants to their places of employment, reminiscent of the domestic life they’d known. African Violets were all the rage. These beauties rose in popularity because they flower all year round and thrive with a modest amount of attention in indoor conditions.

Flash forward to the suburban 1960’s, a space race fueled public fascination with indoor plants was stoked by NASA’s claims that houseplants benefit general wellbeing. Among the most coveted houseplants was the Monstera.

In the 1970’s, the counterculture movement was beginning to macrame itself into the American mainstream. Anti-war sentiment and climate consciousness went hand in hand and plants began to fill homes as a small means of resistance to environmental destruction. Spider Plant and Boston Ferns were among the most popular plants to unfurl in the earth-toned 1970’s homes.

As we barrel into an era of skyrocketing screen times, AI generated everything-under-the-sun, and a collective feeling of disillusion, I think we’ve found ourselves in a place of, once again, reaching for nature. We saw a resurgence of houseplant hobbyists in 2020 during the pandemic– an obvious reaction to more time spent indoors and a search for fulfillment. We reached for each other, too. Online communities huddled together around houseplant care tips, triumphs, and tribulations (we’re looking at you, thrips.)

The throughline that’s carried houseplants through centuries of human history, I think, is the way plants make us feel. Numerous studies have linked indoor plants to physical and mental health benefits. With plants in our homes, places of work, and places of leisure, we see a decrease in stress and increase in cognitive function, mood, and creativity.

Biophilic theory suggests that humans are born with an emotional connection to the natural world– it’s embedded in our biology and doesn’t dissipate, even as more of us spend our lives in urban environments. I would argue that the importance of interior plants has become even more prevalent as humans mainline in technology and urbanization.

In order to get to that biophilic utopia, though, there are certainly improvements to be made. Like most markets in American history, the houseplant industry– from design trends to market dictation– has been dominated in popular media by white, upper middle class individuals. But important conversations are being had about the influence of marginalized individuals on the houseplant industry. The internet has served as a remarkable tool to lessen the barriers to entry of houseplants– some really amazing educational resources exist for any inquiry about houseplants one might have. We’ve dedicated much of our blog to that same mission.

As the houseplant community becomes more inclusive, we can expect to see some exciting new ideas in design and more holistic approaches to care. Much like in the Victorian era, an accessible houseplant industry will give way to more growth than we could have ever imagined.

Until then, happy planting!

Kelly